It’s been called one of the worst places on earth.

With about 9,000 people in a space designed for only a third as many, violence, sexual assault, and suicide attempts are common at the Moria Refugee Camp on the Greek island of Lesbos. Raw sewage flows through the city of plastic tents, which do little to protect their inhabitants from extreme temperatures, and resources are always critically low.

With nothing for the refugees to do but wait—hours for food and water, days for health care, weeks and months for answers on their futures—suffering and hopelessness abound as far as the eye can see.

But just a short drive from this scene of desperation, the rainbow-colored walls of The International School of Peace (ISOP) encapsulate a cacophony of children’s voices singing, counting, and laughing in various languages. Founded in 2017 by two youth movements of educators and activists—the Jewish-Israeli Hashomer Hatzair Life Movement, and its sister organization for Palestinian citizens of Israel, Ajial Movement—the school has become what Seeds of Peace Board Member Bob Bordone called “an oasis amid a living hell.”

Bob was among a group of several Seeds of Peace board members, staff members, and supporters who traveled to Lesbos in December to see an example of the kind of conflict-transformation work in which our alumni are involved. There, they met with Avigail (1999 Israeli Delegation), who is a member of Hashomer Hatzair and one of the founders of the International School of Peace, to tour Moria camp and the school.

Over the course of the day the group observed conditions they described as “bleak,” “inhuman,” and “the end of the earth,” but they also saw echoes of Seeds of Peace: young people, driven by empathy, working for change across political and religious boundaries, instead of waiting for government-led solutions.

Taking Action

At the height of the refugee migration in 2015, some 850,000 people came through Greece, many fleeing wars in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan. They were moved through the refugee camps relatively quickly then, but efforts to stem the flow of unauthorized migration have since slowed waiting periods from a few days to sometimes up to two years.

As the war dragged on in Syria, which shares a border with Israel, Avigail said that it became impossible for her and fellow members of Hashomer Hatzair to ignore the massive scale of suffering that was befalling their neighbors.

“Something very essential that I experienced in Seeds of Peace was to be humble in the face of another person’s life and story. To listen very carefully. To see their pain as my pain, their tragedy as my tragedy as a human being,” she said.

“It reached a point where we said we just could not be silent bystanders.”

And with a shared dedication to lessening the suffering of others, the groups began by collecting food and clothing to send to refugees who had made their way to Greece, but soon realized it was not enough.

According to ISOP, there are currently about 2,400 refugee children on Lesbos, many of whom had never been to school, either because it wasn’t available or they were too young to attend before they fled their home countries. Comprised largely of educators, Hashomer Hatzair soon found a way it could contribute: “Education is what we know, and we wanted to do something with it,” said Roni Huss, a member of the organization and ISOP’s program director.

Together with Ajial, the groups opened the school in partnership with IsraAID in April 2017. It began with two classes and about 30 students, and has quickly grown to a current average of 250 students. They are divided into classes by language—Arabic, French, Kurdish, and Dari—where subjects like math, science, fine arts, and ethics are taught by teachers who are refugees themselves, often from the same countries as their students.

During their visit the Seeds of Peace group met with several of the teachers and heard their stories, like that of a woman who had fled Syria and later tried to return home, only to have to leave again.

“You could see the pain in her eyes, everything she had been through and had lost,” said Tal Recanati, a Seed parent and board member. “But the school has become a very uplifting experience for the teachers. It’s a joyful place, and they’ve been empowered by helping their community.”

While Hashomer Hatzair and Ajial are comprised of educators, the groups decided from the beginning that it was important for classes to be taught by people who speak the students’ mother tongues and who share their cultures. The hope is that teachers will not only become leaders in the camp, but also serve as role models for the students who, like them, are waiting to begin futures in new places far from home.

“This is likely the last time the children will be taught by people from their own cultures,” Roni said. “From here it will be Greek or European educators—that’s not a bad thing, but a lot of times we see immigrants who delete their old culture to become part of a new one. We want to help students build one identity that can hold together the past and the future.”

VAST POSSIBILITIES

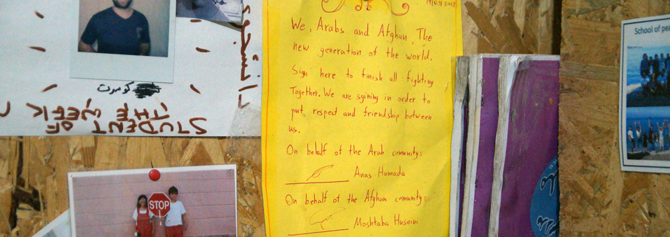

It is not lost on the teachers, or many others who come in contact with ISOP, that the school was founded by, and works with, people who are supposed to be enemies. Whereas fights among the different nationalities are common within the refugee camps, the partnership between the two Israeli and Arab groups has served as a model for the teachers and students from various cultures at the school.

“We’ve had people from Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, tell us ‘if your groups can work together on a school, then we don’t know what to say’,” Roni said with a laugh. “But the thing is that we all as individuals have a lot of power, and there’s even more when we choose to hold hands and act together.”

As successful as the groups’ work with ISOP has been, it is not been without criticism. The founders, who are Jewish-Israeli and Palestinian citizens of Israel, are often asked “Why put efforts in another country, when there are so many problems at home?”

In short, the organizations feel that they have the bandwidth, and the moral obligation, to try to help both.

“There’s no contradiction,” Avigail said. “We are movements of hundreds of people, and we expect to be active in the [Israeli-Palestinian] conflict in the region and in the Syrian conflict to what capacity we can, and we aim to do both.”

The two groups’ work does not erase the complexities that exist between them. But in the same way that Seeds of Peace’s founders knew that recognizing shared humanity could help historic enemies find common ground at Camp, initiatives like ISOP have built connections between the groups, allowing them to create community and resilience on other projects in the Middle East.

“We want to show the world that it’s possible,” Roni said. “The fact that it’s complicated doesn’t mean it’s not possible.”

It’s a lesson that Avigail took to heart at Camp, and that today provides a foundation for her work with ISOP and as a human rights lawyer.

“As a young person at Camp, and then after Camp, I saw that communication, even across borders, can be very natural once there is a platform that allows the communication to happen,” she said.

“People are people. They can connect on many levels, and we don’t have to be afraid from encounters that exist.”

Our more than 7,000 alumni are doing incredible work around the world. Read more of their stories.

Nice initiative. Keep it up.