We often associate summer with adventurous books, maybe because, for many, it’s ingrained since youth as a season of freedom and possibilities.

This edition of What We’re Reading is inspired by the desire so many of us have to seek out new horizons in the summer. And though travel is a privilege that’s not always attainable, the beauty of books is that they allow us to explore all kinds of new terrains, no matter the status of our passports or bank accounts.

From the Amazon to Turkey; the Caribbean to Iraq to the Arctic Circle, these books open up new worlds for both the characters and the readers. Regardless of what the rest of the season holds for you, we hope one of these works will be a suitable sidekick—or navigator—for your next adventure.

Exit West, by Mohsin Hamid

Exit West, by Mohsin Hamid

A young couple, Saeed and Nadia, live in an unnamed city undergoing civil war, from which they are finally forced to flee. Using a system of magical doors, they find themselves searching for sanctuary in Greece, England, and eventually, the United States. This book is as timely as it is eye opening into the experiences of those seeking asylum around the world today. As described in The New York Times, “Hamid does a harrowing job of conveying what it is like to leave behind family members, and what it means to leave home, which, however dangerous or oppressive it’s become, still represents everything that is familiar and known.” — Dindy Weinstein, Director of Individual Philanthropy

Notes on a Foreign Country, by Suzy Hansen

Notes on a Foreign Country, by Suzy Hansen

In this insightful and provocative book, Suzy Hansen interrogates her own narrative and the narratives of America and Americans. Recounting her own experience as a journalist living in Turkey, she uses this book as an opportunity to look inward at her own experience and the myths that make up the American experience. Hansen unpacks the shortsighted and ill-informed conceptions she once held of the Middle East and Central Asia as well as her own misguided conceptions of self, people, and country. Hansen brings to light the overt and subtle ways in which American culture, governance, and military forces have shaped regions and places that she once knew nothing of, but that, for decades, have known a great deal about her, her country, and her people. Her book pushes us to question ourselves and our narratives as a result of being confronted with the often uncomfortable realities of the world we live in and our roles in that world as citizens of the United States of America. — Kyle Gibson, Deputy Director, Global Strategy and Programs

Washington Black, by Esi Edugyan

Washington Black, by Esi Edugyan

This book takes the reader on a journey across the world, and to a bleak past, with a slave boy named Wash and his master’s brother, a naturalist and explorer. By boat, by horse, and by hot air balloon, they voyage throughout the Caribbean, then to the Arctic Circle, London, and Morocco. The story explores the fraught relationship between those who are free, and those for whom the color of their skin prevents them from truly experiencing freedom—despite what local law may or may not proscribe. — Deb Levy, Director of Communications

State of Wonder, by Ann Patchett

State of Wonder, by Ann Patchett

Here is a beautifully told story of a scientist who travels to the Amazonian jungle, in part to research a new fertility drug that allows women to bear children until old age, and in part to figure out the truth of the assumed death of a fellow scientist whose visit preceded hers. Of course, the larger mission becomes peppered with vivid stories of life deep in the jungle and unforeseen discoveries along the way. A joy to read.

— Eliza O’Neil, US/UK Programs Manager

The Flying Camel, Edited by Loolwa Khazzoom

The Flying Camel, Edited by Loolwa Khazzoom

In this anthology of essays and stories by Jewish women of North African and Middle Eastern heritage, each chapter opens a window into the Mizrachi and Sephardi communities, which are often overlooked/erased/discriminated against in the Ashkenazi world. These women challenge the dichotomy of “Jewish” vs “Arab,” bring to light experiences—both positive and negative—that are not associated with the mainstream Jewish narrative in Israel, America, and around the world, and explore their struggle to define themselves in terms of gender, religion, race, culture, and the intersection between them all. In the work that we do, it is critical to constantly reexamine the lines society has drawn between people, and to continuously open our minds to the nuance and complexity of human experience.

— Emily Umansky, Development Associate

The Book of Collateral Damage, by Sinan Antoon; translated from the Arabic by Jonathan Wright

The Book of Collateral Damage, by Sinan Antoon; translated from the Arabic by Jonathan Wright

We begin with an Iraqi scholar, who finds his American life interconnected with his homeland’s past and present after he encounters an eccentric bookseller in Baghdad. A work of fiction loosely based on Antoon’s return to his homeland (Antoon is a professor at New York University) after the devastation of the 2003 Iraqi invasion, it is ultimately a story of all that is lost in war, and I’ve never read anything quite like it: The chapters alternate between the professor’s life and the bookseller’s writings, each of the latter telling the first minute of war from the viewpoint of a completely different being or object, such as a boy who spends his days scavenging among trash; an overworked, aging horse that is nostalgic for the loving care it received as a young racing champion; a living-room wall that witnesses a family grow up and move on. At first the bookseller’s excerpts felt distracting from the scholar’s life, almost like commercial interruptions during a television show—until you suddenly find yourself fast-forwarding to get to the commercials. These chapters made me slow down, look up from the book and take stock of what was around me, and I think that’s the point. Coverage of a war and the concept of collateral damage, as Sintoon told NPR, “makes the massive destruction of lives just an abstract concept. And it becomes like a black hole into which humans, lives, houses, objects—entire lives and potential lives—disappear.” This book does not let them disappear.

— Lori Holcomb-Holland, Communications/Development Manager

What would you add to this list? Any recommendations for future editions of What We’re Reading? Let us know in the comments below, or send your picks to lori@seedsofpeace.org.

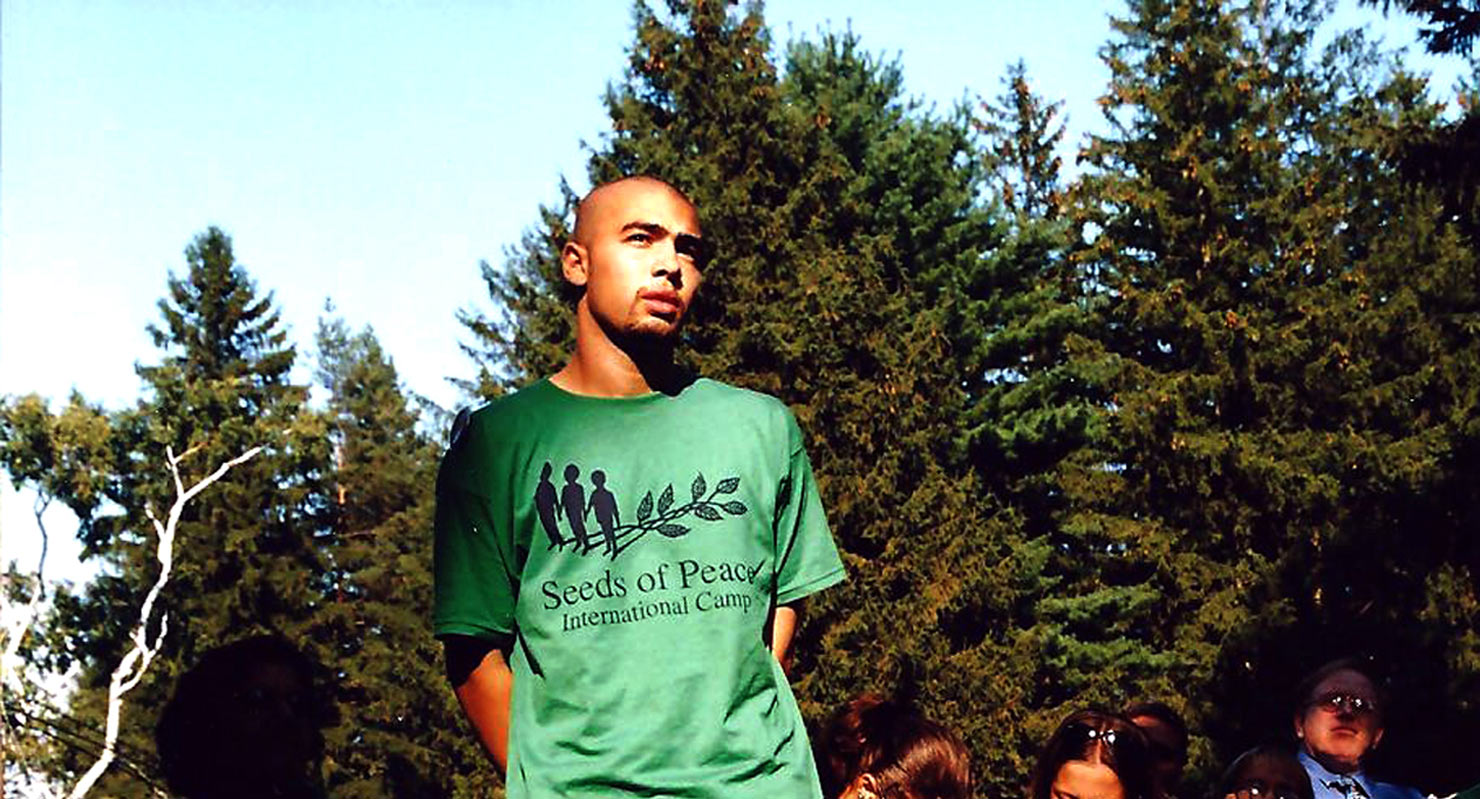

Israeli Noa Epstein, 24, met Palestinian Sara Jabari at a Seeds of Peace camp in 1997. They became pals and even made the dangerous trip to one another’s homes—risking jail in the occupied territories.

Israeli Noa Epstein, 24, met Palestinian Sara Jabari at a Seeds of Peace camp in 1997. They became pals and even made the dangerous trip to one another’s homes—risking jail in the occupied territories. ISRAELI Hamutal Blanc, 16, from Haifa formed a firm friendship with Palestinian Amani Ermelia, 17, at a Seeds of Peace camp in June 2005. Amani lives in a refugee camp in Jericho.

ISRAELI Hamutal Blanc, 16, from Haifa formed a firm friendship with Palestinian Amani Ermelia, 17, at a Seeds of Peace camp in June 2005. Amani lives in a refugee camp in Jericho. PALESTINIAN Mahmoud Massalha, 16, is from north Jerusalem. He made friends with Israeli Amos Atzmon, 16, of west Jerusalem, at a Seeds of Peace camp last year.

PALESTINIAN Mahmoud Massalha, 16, is from north Jerusalem. He made friends with Israeli Amos Atzmon, 16, of west Jerusalem, at a Seeds of Peace camp last year.

After the end of their camp session in July, the delegation of Indian and Pakistani Seeds traveled to Washington D.C to discuss the issues facing both countries and the possibility of peace. Their trip included a reception at the Department of State where they were welcomed by Deputy Secretary of State John Negroponte and Assistant Secretary Richard Boucher.

After the end of their camp session in July, the delegation of Indian and Pakistani Seeds traveled to Washington D.C to discuss the issues facing both countries and the possibility of peace. Their trip included a reception at the Department of State where they were welcomed by Deputy Secretary of State John Negroponte and Assistant Secretary Richard Boucher. Seeds Café this month hosted television and newspaper journalists for a revealing discussion about the role of the media in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The guest speakers for this Seeds Café were CNN Producer Nidal Rafe and Yoav Stern, Ha’aretz newspaper’s Arab Affairs Correspondent. The audience had an opportunity to hear what happens behind the scenes of the media covering the conflict on a day-to-day basis. They addressed the difficulty of having positive stories run in the press and the importance of having local journalists covering events in the region.

Seeds Café this month hosted television and newspaper journalists for a revealing discussion about the role of the media in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The guest speakers for this Seeds Café were CNN Producer Nidal Rafe and Yoav Stern, Ha’aretz newspaper’s Arab Affairs Correspondent. The audience had an opportunity to hear what happens behind the scenes of the media covering the conflict on a day-to-day basis. They addressed the difficulty of having positive stories run in the press and the importance of having local journalists covering events in the region. Please take a moment and help support Seeds of Peace in a simple way—that’s totally free! Seeds of Peace is entered in the American Express Members Project. If everyone clicks on the link below and nominates our project, you could Help Seeds of Peace Win $1,5000,000! All you have to do is click! Every vote counts and the winner receives a $1.5 million grant. Runners up receive between $100,000-$500,000 each!

Please take a moment and help support Seeds of Peace in a simple way—that’s totally free! Seeds of Peace is entered in the American Express Members Project. If everyone clicks on the link below and nominates our project, you could Help Seeds of Peace Win $1,5000,000! All you have to do is click! Every vote counts and the winner receives a $1.5 million grant. Runners up receive between $100,000-$500,000 each!