A new generation of Israelis is now protesting against authoritarian rule. Do they stand a chance?

Israel had never been a perfect democracy. To be honest, it was never even a good one.

Despite everything, there used to be some minimal leadership accountability, some written and unwritten rules of public service, and some class. In the Netanyahu years, however, the rules seemed to change. Israel is no longer a republic; Israel is Netanyahu, and Netanyahu is Israel. As those who oppose him proclaim, he has used every single questionable method, along with mass public gaslighting and psychological manipulations, to deeply engrave this perception and gain increasing power over the years.

With time, Netanyahu was able to eliminate almost every threat to his rule, crushing opponents; silencing critics, and increasingly deepening his control of the media, the Knesset, law enforcement and civil agencies. From schoolteachers, to political leaders, from journalists to judges, those who oppose him are threatened, attacked, marked as traitors or self-hating anti-Semites, and removed from positions of influence. It sometime seems like the entire country is working for Bibi Netanyahu and his followers, known as “Bibists.”

Taking “divide and conquer” one step further, Netanyahu’s method works around the ancient Hebrew word “Shissuy” (שיסוי): Divide, conquer, and convince all parties involved to hate and attack each other.

“But the more they afflicted them, the more they multiplied and grew” (Exodus 1:12)

The COVID-19 crisis, unprecedented unemployment and poverty rates, years of political turmoil and three general elections, along with the Netanyahu trials coming soon, have created a unique opportunity for those who seek change.

An entire generation, my generation, that grew up almost entirely under Netanyahu’s regime, is waking up. There seems to be a sudden realization that the country we thought we had does not exist. It’s a generation that grew up with no hope and no future and has absolutely zero faith in the path this country is headed.

Since the coronavirus crisis started, several protest movements began gaining power and public sympathies, separately, at first. The demonstrations in Tel-Aviv against the proposed West Bank annexation plan grew more significant than expected: A new movement of unemployed and collapsing business owners began growing, and demonstrations against Netanyahu, personally, focusing on his abusive political behavior, his violent propaganda, and incitement, and his corruption allegations, spread wider and wider across the country.

And after an anti-corruption protester who was quite old, peaceful and polite, a war veteran, and a Holocaust researcher was attacked and arrested by police officers in Jerusalem six weeks ago, the protests began to focus on Jerusalem—more precisely, outside of Netanyahu’s residence, on Balfour Street.

Panicking from the rising criticism and the threat to his governance, Netanyahu made a possibly fatal mistake: using the police, the military, and gangs of violent, organized Jewish supremacist “Bibists,” he began terrorizing protesters in the streets. Methods that were usually used against Palestinians, anti-occupation activists, anti-Zionist ultra-orthodox Jews in Jerusalem, and against Black Ethiopian Jews, are now being used against all protesters. The white, secular Jewish sector that traditionally ignored the violence directed towards marginalized communities cannot ignore it any more. Netanyahu meant to scare the new, naïve protesters away, but instead, united them.

“The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them.” (Isaiah 11:6)

After being divided for too many years and now facing a common oppressor, all protests seem to be merging: “Crime Minister” protesters, anti-Occupation activists, together with all groups of political opposition to the government, Palestinian Citizens of Israel political movements, LGBTQ organizations, feminist organizations, climate change activists, peace organizations—and most importantly—an unprecedented amount of people who are not directly affiliated with any specific political organization, who had never protested before, and feel like they have got nothing to lose.

This is the “Siege on Balfour,” a non-violent revolution of love, art, music, solidarity, and new hope. No longer a narrow protest for or against something too specific. This is a wake-up call, and this could be the beginning of intersectional resistance—a rise against oppression of all kinds. It’s a movement with no particular leaders and without any organized set of demands. No speeches are being held, and no stage elevates one person above others. People are standing together with a beautiful mix of chants: “Bread, Freedom, Dignity,” “Justice for Eyad,” “End the Occupation,” “It will not be over until he quits.”

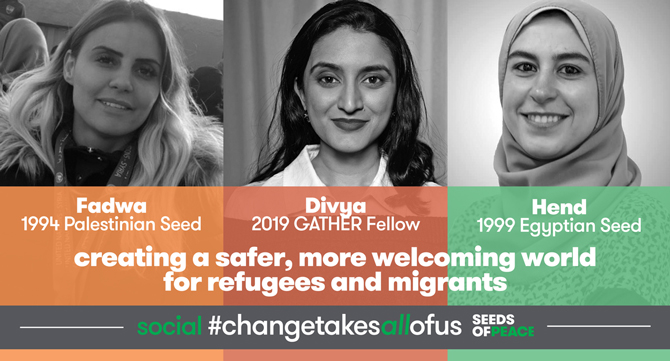

As this movement grows bigger and becomes much more intersectional than we have ever seen before, it seems like more and more Seeds and their families are joining. As a Seed who grew up on the values of solidarity, partnership, and taking courageous steps to bring change, those demonstrations are setting a new example of the Camp motto, “the way life could be.” I have never seen such a movement before in my life, bringing so many people together despite the differences, uniting for such a fundamental change, and standing in solidarity with one another.

With combined powers, does this generation have a chance to change things? Or is it, perhaps, one last pathetic attempt to save our souls? There are many questions as to how Netanyahu will respond to these calls for change and the current moment—and whether the unity of this moment is durable enough to remake and rebuild a country.

Only time will tell, but for the first time in a decade: Netanyahu looks nervous.

What can you, non-Israelis, do to support? Spread the word. Show support to your regime-opposing friends. Balfour protests are now happening four times a week: Tuesdays, Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays. Watch the online broadcasts and share the images of police violence. Stand with your Israeli and Palestinian friends and help them demand this fundamental change for all. Educate yourself and those around you. And pray for us, please.

And then, hopefully, after the dust settles, help us rebuild, rise from the ashes, and create a safe space for all. Change takes all of us.

Jonathan is a 2011 Israeli Seed.

Photo credits (from top): Sharon Avraham and Olivier Fitoussi (Flash90)