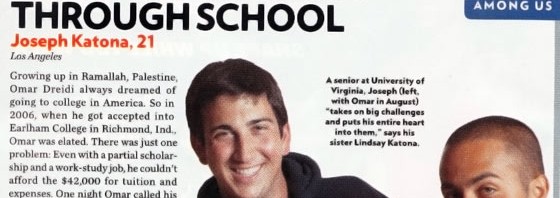

In our 25th year, we’ve reflected upon an entire generation of changemakers who are transforming conflict in their communities.

On May 8 and 9, we celebrated these young leaders with two incredible back-to-back events.

The GATHER Symposium

Our GATHER Symposium, “Innovating for Social Change in Conflict Areas,” began at Facebook’s New York headquarters bright and early the morning of May 8. The event brought together business leaders, social entrepreneurs, investors, and Seeds of Peace supporters to showcase our impact.

Alumni joined figures including Ali Velshi (Anchor, NBC News/MSNBC), Christopher Schroeder (Author, Startup Rising), Yadin Kaufmann (Co-Founder, Sadara Ventures), Lisa Conn (Strategic Partner Manager–Communities-Civic Leadership, Facebook), Georgia Levenson Keohane (Fellow, New America; Professor of Social Enterprise, Columbia Business School), and Nina Nieuwoudt (VP of Product Development and Innovation, Mastercard Labs) in four panels focused on advancing transformative change in communities affected by conflict.

“[Camp] was a lesson in humility and a lesson in humanity … There were lessons I took away that have stayed with me, that are always with me,” said Pakistani Seed and The Nation reporter Amal in a panel discussing the role media can play in transforming conflict.

“As a journalist, the Seeds experience has taught me not to lose my humanity and to write in a way so that the people I’m writing about don’t lose theirs either.”

“There is a drastic need to reimagine business models,” Indian Seed and GATHER Fellow Rishi said during a panel on how private enterprise can foster the conditions essential to peace.

“[GATHER] can provide the genesis of that very important movement to reimagine what a business is altogether, and how capital allocation can go to the right sort of business that make the right sort of impact.”

“I think a lot of us came to Seeds [of Peace] thinking we were going to be Presidents or Prime Ministers. There was this narrow idea of what it means to be a leader, but looking back after 25 years … it really doesn’t matter where you end up in life or what profession you are,” said Israeli Seed and GATHER Fellow Keren (far right) in a panel on how leaders across sectors can be catalysts for change.

“It’s not about being a politician around the negotiation table for the peace process; it’s about really thinking how you can do everything with intent. That intent is something that follows us throughout our different choices in life.”

SYMPOSIUM PHOTOS

25th Anniversary Spring Benefit

The next evening, over 1,000 people joined us to celebrate at Chelsea Piers.

One of the highlights of the night was hearing from Vice President Joe Biden, recipient of the John P. Wallach Peacemaker Award.

“Seeds of Peace helps break down the impulse for the impersonal and the knee-jerk stereotypes that are easier to cling to; the desire to dehumanize what’s different and the mindset that frames the opposition as the enemy,” Biden said upon accepting the award.

“Ultimately, no progress is ever made without starting a conversation, beginning to challenge some of the misconceptions, listening to the other person, and ultimately being willing to talk to people you really disagree with.”

Biden ended his speech stressing the need to continue furthering our impact amid the current climate of division: “The work of Seeds of Peace is more important than ever, especially today when it is all too easy to become disheartened, when it is tempting to give into cynicism, and when it is easy to doubt our capacity to change the way we think or the way we interact.”

In what may have been the most moving part of the night, Seeds in the audience stood up to reflect on how their experiences with Seeds of Peace inform who they are today.

“Our Seeds are resilient, and are saying ‘No!’ to the racism, violence, and injustice they are living in,” Palestinian Seed Mirna declared in her remarks. “I am here to let my community know that nothing we do at Seeds of Peace is normal. We are here working hard to change the status quo.”

“We have to be the ones who say, ‘Talk with me, I’ll listen,’ because only if we listen with an open mind will we understand power and privilege, fear and anger,” remarked American Seed Jackson. “Only then can we move beyond stereotypes and bridge divides. Only then will we be able to ignite change.”

Other highlights included the unveiling of the Tanner Big Hall at Camp in honor of the Tanner family, a silent auction, hilarious stand-up from Seth Meyers, and an amazing performance by Hamilton’s Mandy Gonzalez—who was joined by our own Seeds Singers!

What benefit would be complete without an after party? Our community capped off the night of celebration by dancing to the beats of musicians from the Middle East, including Palestinian rapper SAZ, American Seed Micah of the Jerusalem Youth Chorus, and GATHER Fellows Sun Tailor, and Mira Awad.

Reflecting back on those whirlwind two days, one thing stands out in particular: What made these occasions such a great success was not only how they highlighted our quarter century of leading change, but how they also set a strong course for the next 25 years.

As we look forward to Camp this summer and to our programs beyond, there’s a renewed commitment to our mission in knowing that our work will continue to inspire young leaders for many years to come.

Watch the full video of our 25th Anniversary Benefit—and check out our photo album of the event below—to get an extra taste of the evening’s impact!

SPRING BENEFIT PHOTOS