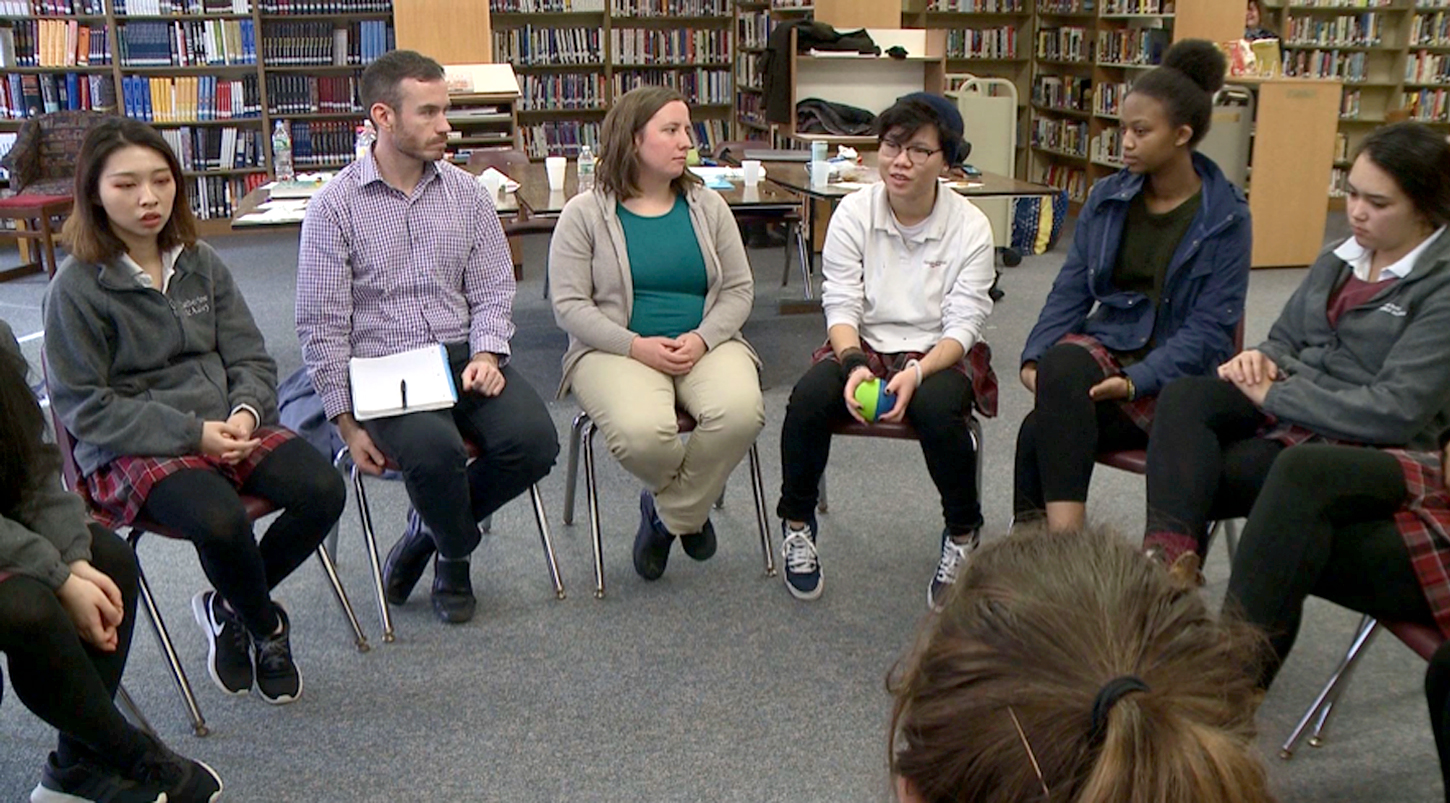

PORTLAND | In late November, 36 Maine Seeds attended the second in a series of workshops on race. Following up on discussions from their previous workshop, the activities and dialogues on November 22nd went deeper into conversations on privilege and power, and how they are related to race. The workshop helped the Seeds process their own emotions and reactions to the recent events across America, and more particularly, to the events taking place in the community of Ferguson.

The first activity that the Seeds participated in was an exploration of words like “Racism,” “Stereotypes,” “Power,” “Privilege,” and prevalent phrases and hashtags like “#handsupdontshoot.” Afterwards, one of the Program Coordinators led a short session on the difference between societal and personal power. The Seeds investigated what they could do to alleviate injustice in their home communities and on a peer-to-peer basis.

White Seeds and Seeds of Color also split into small group dialogues that were separated by race, because it allowed for them to carry on their discussions in ‘safe spaces.’ All of the Seeds then reconvened and engaged in conversations with a Seed of the opposite race, covering topics from law enforcement to their personal feelings about their place in society.

Throughout the day, many of the Seeds pushed themselves to step out of their comfort zones. It was evident by the end of the workshop that many of the Seeds had begun to find and embrace their own voices. The impact of the workshop has been evident in the community-based response of the Maine Seeds. Seeds in Lewiston are involved in a #blacklivesmatter movement at their school and have successfully had their protest posters approved by their administration. Seeds at Deering High School held a walkout and a die-in. Furthermore, Deering, Scarborough, and Portland Seeds are currently working on getting together to have a dialogue on race, and are hoping to eventually include superintendents, administrators, and teachers in that discussion very soon.

Maine Seeds Pricillia and Naissa

Maine Seeds Pricillia and Naissa