NEW YORK | The Seeds of Peace Young Leadership Committee will present the 5th Annual Bid for Peace Celebrity Auction on Tuesday, January 14th at 6:30 p.m. at the Hammerstein Ballroom at the Manhattan Center in New York City. This year’s event will be hosted by Actress/Comedian Janeane Garofalo with special guest, The Honorable William J. Clinton, 42nd President of the United States. The Barenaked Ladies are scheduled to perform live at the event and receive the first-ever MTV Networks Seeds of Peace Award.

Honorary Host Committee members who are lending their support for the evening include:

- Kim Cattrall

- Chevy Chase

- Billy Crudup

- Kelsey Grammer

- Robert Sean Leonard

- Bebe Neuwirth

- Chris Noth

- Mary-Louise Parker

- Susan Sarandon

- Sam Waterston

- Pinchas Zuckerman

In addition to the live musical performances and surprise celebrity guests from television, film and sports, the event will feature over 200 premium live and silent auction items (live action conducted by C. Hugh Hildesley, Vice Chairman of Sotheby’s). Auction highlights include:

- Cruise through the Greek Isles aboard Princess Diana’s yacht

- “Dream Week” with the New York Yankees

- Gourmet dinner party prepared by Union Pacific’s world-renown chef, Rocco DiSpirito

- Slumber party at Dylan’s Candy Bar

- Getaway to a romantic South of France villa

- Original artwork by Ya’akov Agam

- Custom dress designed by Nicole Miller

- Private basketball clinic with an NBA star

Israeli and Palestinian Seeds of Peace alumni will also speak and pay special tribute to John Wallach, the founder of Seeds of Peace, who passed away in July 2002.

Package tickets for Bid for Peace Celebrity Auction start at $1,500 and include a VIP reception with President Clinton. Individual tickets are available between $175-$500. Tickets can be purchased online at www.seedsofpeace.org or by calling Seeds of Peace at 212-573-8040.

To further advance its objectives, Seeds of Peace has formed the Young Leadership Committee, a New York-based group comprised of young professionals (25-45 years old). Each year, the Young Leadership Committee holds a large fundraiser, raising important funds and exposing more people to the work of Seeds of Peace.

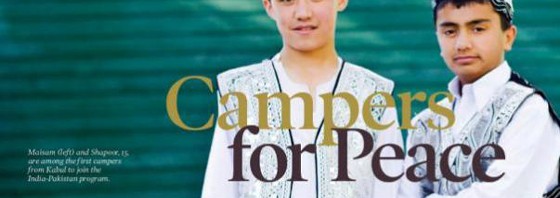

Since 1993, Seeds of Peace has graduated more than 2,000 teenagers representing 22 nations from its internationally recognized conflict-resolution program. The Seeds of Peace program brings hundreds of youth identified by their governments as among the best and brightest to live together at three consecutive month-long summer programs. Through the summer-long programs, participants develop empathy, respect, communication/negotiation skills, confidence, and hope—the building blocks for peaceful coexistence.

ADDRESS: Manhattan Center, 311 W. 34th Street, New York, NY 10001

DATE: January 14, 2003

TIME: 6:30 p.m.

LOCATION: Hammerstein Ballroom

CONTACT: Rebecca Hankin | (212)-573-8040 ext. 31.