LAHORE | Even in the best of times, it takes a lot of planning, care, and skill to create a space where people can grow; where they can challenge their perspectives, make mistakes and know that their peers—even those whom they barely know—will pick them back up.

To build that type of trust across lines of difference, and hundreds of miles of distance, is a whole other challenge.

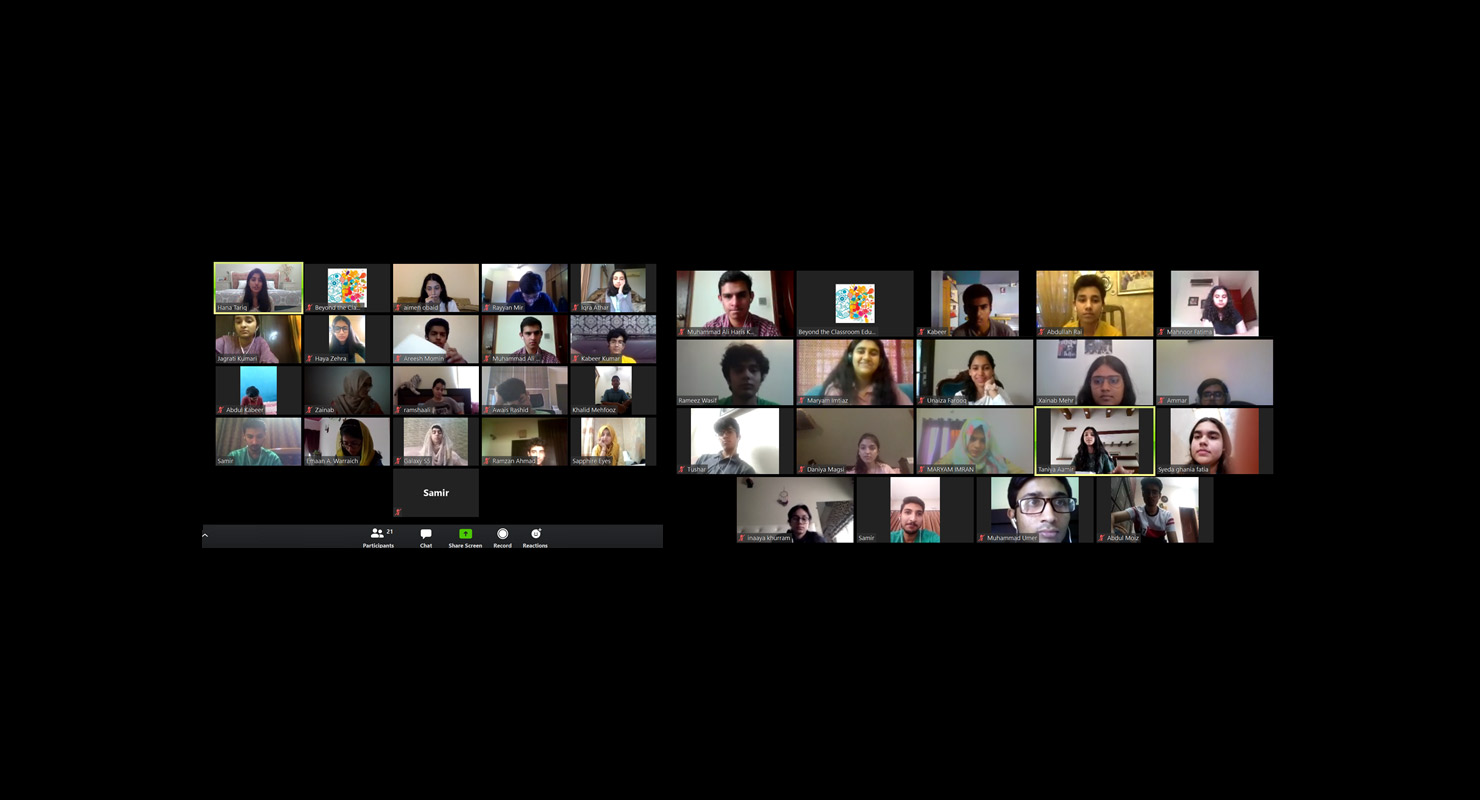

This spring, eight Pakistani Seeds from Lahore and Karachi showed that not only were they up for the task, but they were ready to take on more. In April, they held the first edition of Evaluating Perspectives, Identities, and Cultures (EPIC), a free of cost, Seed-led program centered around dialogue exploring different provincial identities in Pakistan. It went so well that they’re currently planning a second edition for July, 2020.

“The first successful run of the program was mind blowing to me,” said Ali Haris, a 2018 Seed. While he said he previously believed that dialogue couldn’t effectively be conducted online, “seeing people’s lives impacted and changed toward the end of the program broke the false notion I held.”

Over the course of five days, the Seeds led participants in activities and dialogues that were designed to help participants engage with their identity and question their preconceived notions.

Approximately 150 teenagers applied for the April program, and the selected 28 attendees spanned different socio-economic lines and identities from four different provinces in Pakistan.

“We live in an environment that heavily affects who we are and who we become,” read the students’ description of the program. “Our identities are a reflection of not only the micro environment, but also the macro environment, and it’s absolutely essential to understand who you are through the lens of culture, values and norms that are shaped provincially and nationally. We invite you to have a dialogue around it, and do it, the Seeds of Peace way!!”

Despite the students having schoolwork, internet connectivity issues, other personal commitments, and even family members battling COVID-19 infections, the Seeds worked tirelessly to pull off the program, and the students showed up every day to delve into difficult questions.

“It was one of the better virtual programs I’ve seen among 14- to 16-year olds,” said Hana Tariq, head of curriculum for Beyond the Classroom, which partners with Seeds of Peace to run local programs in Pakistan. “I feel that it started with awkwardness on the first day and ended with hope to meet each other as soon as the lockdown ends. There was willingness to learn, to experience, and to open up.”

While having to run the program virtually came with its challenges, it also made the program accessible to students who might not have been able to participate otherwise.

“Probably 70 percent of the participants wouldn’t have come had it not been online because they would have had to travel so far to attend,” Hana said.

Highlights of the week included learning directly about what it means to live in Kashmir under occupation from a student who had spent much of his life there, as well as a day where Seeds from India were invited to participate in dialogue.

For Ali Haris, another particularly impactful moment brought him back to Seeds of Peace Camp in Maine.

“One of the participants who previously held a conservative view about an issue actually challenged herself and went to educate herself on the topic,” he said. “That was one moment when I realised how similar it was to the light-bulb moments that happened to me at Camp, and showed me that you can definitely make a huge impact through a virtual connection.”

If the participants’ feedback were any indication of the program’s success, the Seeds, who attended the Seeds of Peace Camp in Maine in 2015-19, clearly hit the mark. Multiple participants thanked the Seeds for creating a safe space, “where you can talk out your heart and without fear,” wrote one participant.

“The facilitators did such good work in collaborating with us and making us think critically and innovatively … the way they made us question ourselves—our perspectives, identities, conscience, and ideas—it has made us more confident about our true identities,” the participant wrote.

The team members (which includes nine Seed this time: Xainab, Awais, Ali Haris, Fatima, Mariam A., Mariam R., Samir, Rameez, and Taniya) were part of a group of Seeds that traveled to Turkey last year to participate in a facilitation and mediation course.

The EPIC course was formed out of a desire to pay forward what they learned from that four-day workshop, Hana said, as well as an exercise in leadership: a chance to see how projects come together, to learn how to express an idea, to work through disagreements within a team, and to try —and succeed—in challenges they previously didn’t think possible.

“Neither me nor any of the team members had any prior experience designing curriculum,” said Xainab, a 2017 Seed.

“We had to be thorough and careful. It required long hours and re-reviewing everything a 100 times! But our expectations were exceeded in terms of how much the group grew in only a span of five days! Seeing those speak up who didn’t speak as frequently and seeing some of the participants who did speak frequently create space for others, for example, was something that was very rewarding for us to see.”