Twenty-five years ago, I was born in a refugee camp in Kenya after my parents fled the civil war in Somalia. My parents struggled to keep my brothers and I secure, fed, and sheltered.

Our struggle became even worse when my parents decided to divorce, divide the children they had together, and go their separate ways. I went with my father.

By the age of 6, I already had the responsibilities of an adult. I had to cook, clean, and look after my little brother while my father left to search for food. The shelter we lived in was slowly tearing apart. Every day, wild animals like hyenas and lions would dig, rip, and damage it, exposing us to the elements. Hope was slowly leaving our hearts.

But then, a miracle happened. After years of feeling hopeless, we learned that the United Nations had selected our family for resettlement to the United States. Friends and neighbors spoke highly of America and told us we were going to a place that was heaven on earth. We were extremely excited for the opportunities our new life was going to offer us. We had been given a second chance.

In September 2005, we were resettled to Syracuse, New York, one of the poorest cities in the nation, especially for black folks. We were nervous and unsure how to make use of the resources that were available. Paying monthly bills was a new idea to us. We did not know where to look for food and when we found it, our bodies rejected much of it. The only thing that tasted familiar was candy. It was a completely new world.

We were given a home in an area Syracuse people know as the Bricks. It was also known as the hood or the projects. We didn’t know what the “hood” was or what it meant to live in one, but we were confident that it was going to be better than the refugee camp we came from.

I was excited to go to school. Unable to speak the English language, I used basic senses to understand and communicate with my peers. After my first week of school, I was bullied by a classmate. At the time, I was naive and did not realize I was being bullied. I comprehended the situation as a way Americans communicate and thought that it was a weird way to make a new friend.

From the time I began school, to the time I went to college, I lost count of the number of times I was attacked. I soon learned that the people attacking me were affiliated with gangs. They had guns and were not afraid to use them. At night, I would hear gunshots near my house. In the morning, as I walked to the area where the bus picked me up for school, I would see a trail of blood on the pavement from someone who had been wounded.

As I began to understand English, I realized I was not safe from verbal attacks either. I was treated like a criminal based on my skin color. People called the cops on my friends and I, when we hadn’t done anything wrong. I learned to avoid looking like a Muslim whenever there was an attack on American soil. l was made to feel that coming to America as a refugee who seeks asylum is the worst thing you can be. People automatically concluded that you had come to take away their American Dream. All of the ignorant, negative stereotypes that were associated with coming from a refugee camp in Kenya were hurled in my direction. Once, a fellow classmate scraped cookie crumbs off of her desk and into her palm after eating a cookie and tried to hand me the crumbs, suggesting I should eat them. It was the most dehumanizing incident I’ve ever experienced in my short life, one I still struggle to forget.

This was not the America I was told about back in the refugee camp. I began to hate who I was and where I came from because of the way people treated me. As a result of these experiences, a small, negative voice developed in my mind, which gradually got louder. It was saying things such as ‘You are nothing. You deserve nothing. You are a burden to people; you are worthless.’ I could not turn it off. I was feeling mental pain that hurt more than physical pain. I didn’t know what it was but I wanted it to stop.

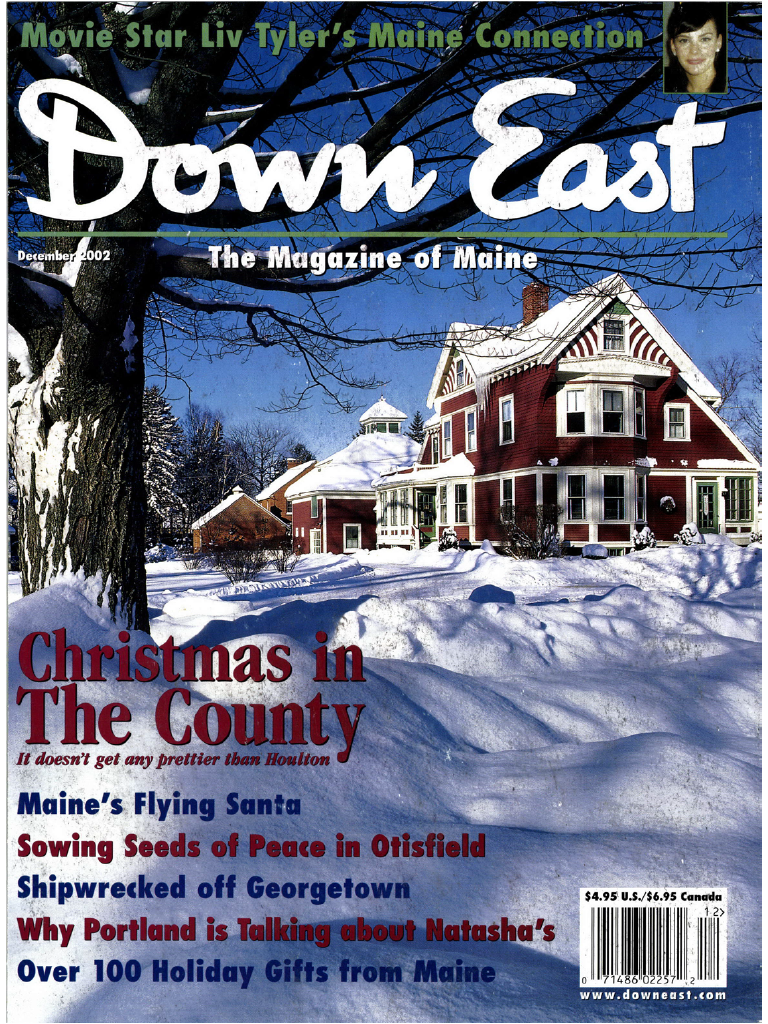

But then another miracle happened. I learned about Seeds of Peace. I didn’t know what it was, but I liked the word ‘peace’ in the organization’s name. My brothers told me it was a place where we could water-ski and play soccer every day. I went to the introductory meetings held after school. It sounded amazing and just what I had been yearning for and from the moment I set foot on the Camp’s grounds, I knew a journey of self-discovery and transformation had begun.

In the dialogue hut, I was given the space to unbottle all of the things I had bottled up over the years. I allowed myself to venture out of my comfort zone, to try new activities and to learn more about myself and others. Although I am normally a reserved and shy person, I found myself singing and dancing in front of people in an uninhibited way. I bonded with people from different socio-economic, racial, and religious backgrounds over bonfires and s’mores. I was made to feel that I was enough, and that my difference was beautiful. It was the happiest three weeks of my life.

There’s a saying at Seeds of Peace: out beyond ideas of right-doing and wrong-doing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there. I learned that people in this field look beyond labels of society. They use the “I” statement when they speak and not “they” or “them.” They delve into the most challenging topics fearlessly in the hope of growing past their comfort zone. They listen with their whole bodies even when they disagree with what is being said. They love with their whole hearts and help each other dismantle and heal from past experiences. This was an unreal experience. Unknowingly, it was what I had been searching for my whole life. It refurbished the hope that had been damaged by the outside world. Seeds of Peace became the place I call home.

Today, I work as a substitute teacher in the public schools of Syracuse and use every opportunity to mentor, educate, and empower students to become more than what the hood offers. I am on the board of directors for a non-profit that connects new Americans to the resources that help them transition into their new life. I am also on the board of a local non-profit credit union that helps fight off big banks that make poor communities poorer and works to keep the community’s money within the community. And I am working on a documentary that helps people understand what it means to be a refugee in America.

For as long as I walk this earth, I plan to keep what Seeds of Peace made me feel in my heart and use it as a hope for what this world can one day become. No matter where life takes me, I plan to live by the late Camp Director Wil Smith’s words and do “whatever I can, with whatever I have, wherever I am.”

Excerpt from remarks delivered at the 2019 Spring Benefit Dinner on April 30 in New York.