In every force of nature—a thunderstorm, a blizzard, a wildfire, a tornado—there exists the possibility of destruction, as well as the opportunity for change.

So when an abundance of childhood energy earns you the nickname “The Hurricane,” you can try to suppress that force, or you can channel it for good.

“Maybe I had more energy than people around me knew how to hold. I often felt like my energy was used as a weapon against me, like, ‘hey, calm down, sit down,’ but I don’t see it as a negative thing anymore,” Monica, a 2019 GATHER Fellow, said. “It was just a lack of creativity on other people’s part.”

There is no shortage of creativity in the ways that Monica is using her energy to make change today. As a founder of the nonprofit group Activate Labs, she is essentially using every tool she knows to shift power.

Whereas much of the work done around humanitarian aid or international development focuses on things like food, clothing, jobs, and shelter, Monica’s interests lie in addressing the needs that can’t be seen or touched.

What that looks like in person can vary, but it typically means showing up—always by invitation of local people or organizations—to the frontline of a community impacted by violence, trauma, or conflict. There, the process is guided by design thinking to develop a peacebuilding process that puts the people who would be benefiting from a program or service at the heart of creating and implementing the solution. In short, they’re focused on helping communities take back power over their shared futures.

“Having agency is just as important as giving them technical skills like building capacity. All of that is fine, but the confidence of knowing that you have the power to solve your own problems—to have that control of your world, that vision of your own future—not a lot of people have that, especially people who have experienced violence or oppression,” she said.

“The key to our process is that we consider non-tangible human needs, like belonging or community, nurturing relationships, transcendence, freedom and power in your own world. We believe that when these things are met, then you can actually work in the community to find jobs.”

In some places, this may be in the form of workshops and trainings. Such projects have included transformative leadership training sessions for over a thousand women in Mexico, as well as working with Get Up and Go Colombia—a group that promotes tourism in parts of Colombia that were affected by armed conflict.

For the latter, Activate Labs was contacted to co-design a peace process for a group whose expertise wasn’t in peacebuilding, but that wanted to take a human-first approach to addressing unemployment, a problem that is shared by all those impacted by the country’s civil war. The workshop began by bringing together 45 ex-combatants, as well as those who had trouble finding work because they had been displaced, injured, or in some way affected by violence, and worked toward giving participants the ability to name the problems in their community, and decide what peace tourism and working together could look like.

“There are a lot of solutions to unemployment, but this is a chance to create something together from the beginning—to seek buy in early on and build community,” she said. “People are able to define their own problems and lead their own change, and for peace that makes the most difference because it’s all about shifting power.”

SPACE FOR PEACE

Before peace design takes place, it’s often preceded by another of Activate Lab’s specialities: a peace activation, a peacebuilding response to crisis, violent conflict, or social disruption where the focus is placed on the needs that can’t be seen or touched.

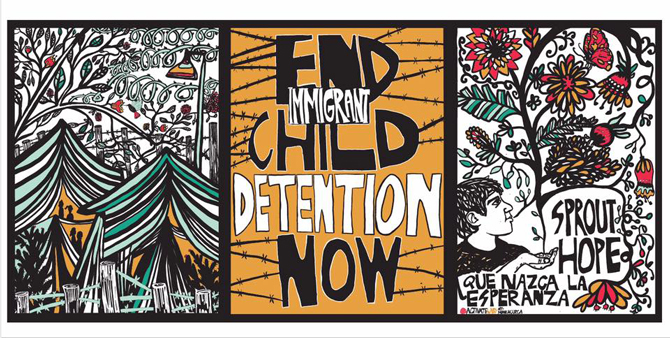

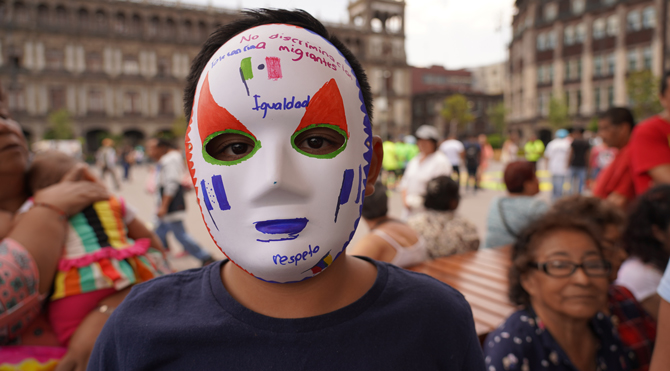

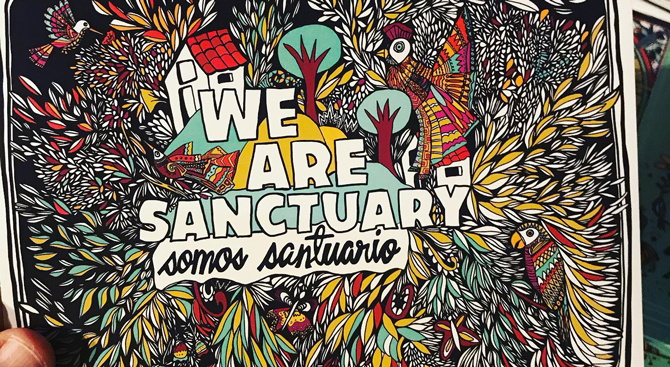

In the past year Activate has led over 20 such peace activations, where they literally take up public, politicized space—such as public plaza in Mexico City, or near one of the largest and most infamous migrant detention centers in Texas—and infuse it with a festival-like atmosphere complete with activities such as karaoke, dancing, face painting, and communal art projects. Some of these locations are places where even the most basic human needs are rarely met, much less the intangible ones.

“In the same way that violence and policies that cause pain aren’t accidents—they’re engineered—we can design peace and bring what’s valuable and important into a public space through a creative and arts-based message,” she said.

She spoke of an event a few months ago, just around the time when the world was learning of the deplorable conditions in the U.S.’s migrant detention centers, when Activate Labs organized a peace activation outside one such detention center in McAllen, Texas. A young boy, maybe 5 or 6 years old, whom she said was among the children who had been separated from their families at the border, stood in line to get pizza at peace activation.

“So the kid finally got his pizza, I’m standing by the banner we brought for an art project, and he literally looks up at it and says ‘whoa.’ He hands me the pizza and just starts coloring,” Monica recalled. “The idea that self expression is not a powerful human need is just foolishness. Creative expression and the chance to see our problems from a different place—that’s something we need, and when we don’t have it, it’s more precious than food.”

AN EARLY CALL TO ACTION

Whereas many of Monica’s friends growing up decorated their walls with pictures of teen dreamboats ripped from the pages of TigerBeat magazine, Monica’s were adorned with pictures of orphans and starving children from the pages of National Geographic.

“I have always known my calling, even when I was 12 years old,” she said. “I didn’t have all the tools for understanding, but I wanted a place for these kids and I wanted to think about them.”

The youngest of 11 children, her family emigrated to Southern California when she was 5, having left their home in Communist Romania where they faced religious persecution. Growing up, she said her father modeled what it meant to live an empathetic life—she vividly remembers one occasion of him serving a fancy meal to roofers who were working on their house—and she said short-term service trips with her church gave her the chance to gain a sort of perspective that many 12-year-olds don’t have the opportunity to experience.

Today, Monica is trying to make the work she does a normative experience for her own two children; she said that her daughter, who is 9, has come to border towns to visit refugees with her many times in her short life.

“She’s been a part of people’s healing because she’s a cute girl and she’s funny, but she ‘gets the memo’ that these are humans,” Monica said. “It’s creating a culture of treating people differently, and it’s very intentional.”

Her work frequently keeps her on the go. She gave this interview during a break at a conference in Cancun, Mexico, and a few days later would be leaving for another in Kenya. She currently has projects running in Central and South America, and over the summer, Monica, her kids and her husband—whom she credits with making possible the global nature of her work—recently left Southern California for Washington, D.C. to be closer to a greater concentration of peacebuilding organizations.

She believes Activate Labs is at a critical juncture—its services are in demand and people are eager to join in on its efforts—but as with many grassroots organizations, how to take the group to the next level isn’t so clear. This is a large part of what brought her to GATHER.

“You can feel it—we need to grow because this kind of empathy and centering around people who are impacted is needed in the world. I know more people want to be a part of it and I need to figure out a way to grow for that reason,” she said. “What GATHER gave me is the inertia to think bigger.”

Among her big concerns is keeping in line with their values as they grow. She spoke of a recent incident where she was contracted to do consulting for a government peacebuilding organization, but the arrangement fell through because of their work with migrant caravans and fears that she might be too liberal of a partner while the Trump administration is in the White House.

And while she pondered whether she should erase all of her social media and references to ending the separation of migrant families, she received wise counsel from a friend:

“He said, ‘You probably won’t get business relationships you want because of who you are, but you’ll get the relationships and opportunities that you need because of who you are,’” she recalled. “That gave me solace.”

Perception is at the heart of so much of the work Monica does, and core to that is taking what could be seen as a hindrance—whether it’s pain of the past, anxiety, or being a hurricane of energy—and channeling it toward the good. When asked what keeps her up at night, she pushed back against the idea that such a level of anxiety was normal or okay, and shifted it to what she saw as a more valid question.

“The real question is what keeps me going, and I’m passionate about shifting power and getting to a place where we can see each other, and how we work in this world is kind and compassionate, and giving and open,” she said. “Anxiety is useless toward the good; it takes on a velocity-filled form and becomes a force of nature. My passion for peace is a force of nature that someone will have to deal with.”

This series highlights our 2019 GATHER Fellows. To learn more about the inspiring social change that Monica and our other Fellows are working towards, check out #FollowtheFellows on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.