They came together across borders and often-unreliable internet service, through artistic differences, countless Zoom meetings, delays, and cancellations wrought by a global pandemic.

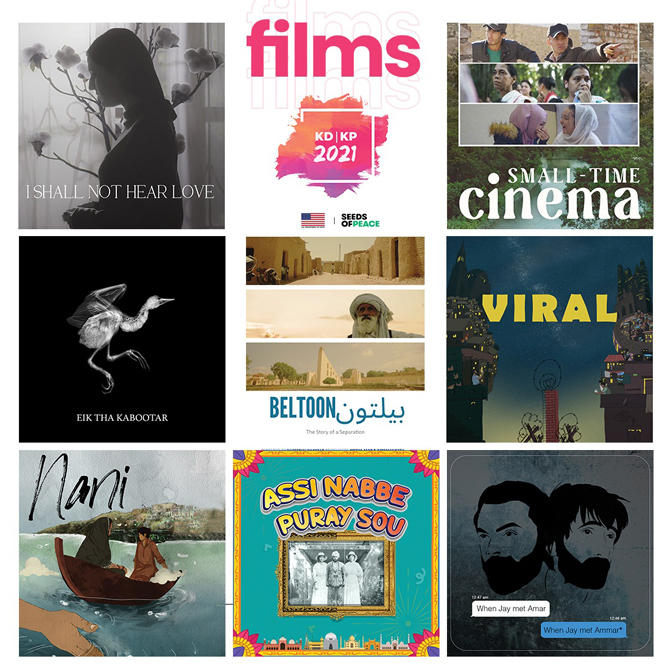

And in July, the 42 emerging filmmakers from India and Pakistan finally came together to celebrate the eight short films they had created as part of the first ever Kitnay Duur Kitnay Paas—an initiative sponsored by the U.S. Department of State and implemented by Seeds of Peace.

“It was definitely one of the most beautiful moments of my life,” Haya Fatima Iqbal, one of the program’s three mentors, said of seeing the participants finally meet in person in Dubai for the film screenings, dialogue, and workshops.

The program was conceived by John Rhatigan, Cultural Affairs Officer at the U.S. Consulate in Karachi, with the goal of promoting peaceful connections between India and Pakistan by bringing together young visual storytellers to create short films.

“While the cultures of India and Pakistan are deeply connected, opportunities for people of both countries to interact can be limited,” Rhatigan said. “Programs like this one build greater connection and understanding.”

Beginning in October 2020, the call for emerging filmmakers ages 21-35 attracted hundreds of applicants with stories to tell. The final selected participants—21 from India and 21 from Pakistan—were brought together virtually for the first time in April 2021, where they were able to refine and build on their ideas, stories, and skills with the guidance of experienced filmmakers who served as mentors on the project: Haya Fatima Iqbal, an Academy-Award winning filmmaker from Pakistan; Sankalp Meshram, a five-time National Award-winning filmmaker and educator from India; and Marcus Goldbas, a 2007 American Seed, filmmaker, and educator at the University of Virginia.

The 42 participants were then divided into eight cross-border teams and tasked with pitching story ideas that had two primary criteria: They had to be filmed on both sides of the border and have themes of universal friendship between the two countries. The mentors selected one topic for each team, and over the next few months, the filmmakers finalized their stories and began to bring them to life.

The project’s name, which translates to “So Far, So Close,” in both Hindi and Urdu, captured the feeling described by many of the participants.

“I had never interacted with anybody from Pakistan, let alone for a creative project like this so that was also a very unique experience for us and just a huge learning curve,” said Akshaya, an Indian filmmaker whose team created “When Jay Met Ammar.”

Often drawing from their own lives and communities, the filmmakers created narratives and documentaries that take viewers across well-known and unexpected corners of India and Pakistan. Along the way, they often weave together the past and present, depicting aspects of people’s lives touched by the interconnectedness—and divisions—of the two countries.

They include films like “Nani,” in which a boy in Pakistan tries to help his grandmother fulfill her final wish by taking her to a Pakistani town that looks so identical to her childhood village in India that she is at last satisfied. And “Eik Tha Kabootar,” which explores fears surrounding the border through the true, and often humorous, story of a Pakistani pigeon keeper who names his birds after Bollywood stars.

They show two brothers split across the border; a Kakar Muslim man waiting for his Hindu neighbors to return; a family treasure divided by countries. They show the dreams of storytelling from small rural towns, and the reconnection of lost family and friends.

While the films explored diverse lives across the border as well as within India and Pakistan, at the same time, many of the characters find that they are more similar than different, more connected than they believed.

It was a lesson not lost on the filmmakers themselves.

“We need to support the people that are different from us, rather than constantly fighting, making everything a single kind of color, trying to make a nation a homogenous nation,” said Priya, one of the Indian filmmakers behind “Small Time Cinema.”

The film project is the latest in Seeds of Peace’s long history of working with and through art to connect people and create pathways to peace.

“The film project is exciting for many reasons, but most especially because it bridges proven people-to-people methodologies with powerful new technologies that have the ability to motivate and move the masses,” said Joshua Thomas, executive director of Seeds of Peace. “Here, participants were able to not only share their stories with people they may have otherwise never met, but to also create new stories that can reach hundreds of thousands of people, and that can open eyes to the past, and change minds about what the future can be.”

While the films don’t show the late nights, last-minute set changes, and creative problem solving of the teams, they serve as records of the collaboration, openness, and commitment of each of the filmmakers. Each team faced tremendous challenges, and in the end, created something better because of it.

“If left to themselves, people can find a way to interact with each other, to communicate with each other, and to like and love each other,” said Sankalp. “The success of KDKP shows that if you create such platforms where people can interact, if you let people talk to each other, if you bring people closer together, magic will happen.”

The films debuted June 22 with simultaneous screening events in India and Pakistan, and have since been viewed thousands of times each on YouTube and as part of film festivals and cultural screenings in South Asia. They are available to view on the Seeds of Peace YouTube channel through September 1, after which they will be available to view through film festival websites. Learn more about the participants and the project at kitnayduurkitnaypaas.com.