There are few septuagenarians who could inspire the sort of rock-star status among a gaggle of teenagers that Bobbie Gottschalk does at the Seeds of Peace Camp in Maine.

Sightings of the diminutive, gray-haired grandmother—always adorned with a baseball cap and a camera around her neck—are often met with squeals of delight, and requests for hugs and photos with and by Bobbie. And she gladly obliges; each photograph is another chance to connect with campers, to hear how they’re feeling, what’s bringing them joy, what’s causing them concern.

In more than a few ways, her camera is a natural extension of what she does best: She sees people.

Whether it was seeing the potential in John Wallach’s idea to create a camp that brought together kids from the Middle East, or the reason one camper might be standoffish in group activities, or the heights that young Seeds and staff could reach if given the chance, for nearly three decades Bobbie has seen people not just for who they are, but for who they could become.

“Bobbie gave me the most important opportunities in my professional life and supported me through many of the most challenging moments we faced in building the Middle East regional program and keeping its spirit alive through profoundly difficult times,” said Ned Lazarus, a former counselor at Camp and Middle East Program Director. “I owe my entire career, and much of what I’m proud to have done in my life, to her faith in me and my ability to contribute to this community.”

Since her days as the first executive director of Seeds of Peace, she’s been a steady source of hope, encouragement, and guidance for Seeds of Peace staff and alumni alike. And while she could spend her golden years in the comfort of her family’s vacation home, every summer since 1993 she has faithfully returned to her small cabin at Camp—among the mosquitos, ticks, rain, and heat—where she’s embraced a new purpose: documenting the daily ins and outs of Camp, using her personal social media accounts to keep the organization’s alumni connected, and embracing the role of the loving-but-firm grandmother for campers, counselors, and 7,300 alumni.

“In so many ways Bobbie is all of the things that we as an organization strive to embody,” said Leslie Lewin, executive director of Seeds of Peace. “To say that Bobbie is the connective tissue of Seeds of Peace is an understatement; her impact on the organization and thousands of Seeds is immeasurable.”

AT HOME WHILE AWAY

The walls of Bobbie’s neatly-appointed cabin at Camp are a patchwork quilt of memories, adorned with photographs of her with Seeds and various staff from over the years, and, of course, turtles. Bobbie has long had a tradition of giving a necklace with a turtle charm to second-year campers, known as Paradigm Shifters, or P.S.s. It’s a small reminder that Seeds of Peace is the home that the campers will always carry with them, just as everywhere a turtle goes it carries its home.

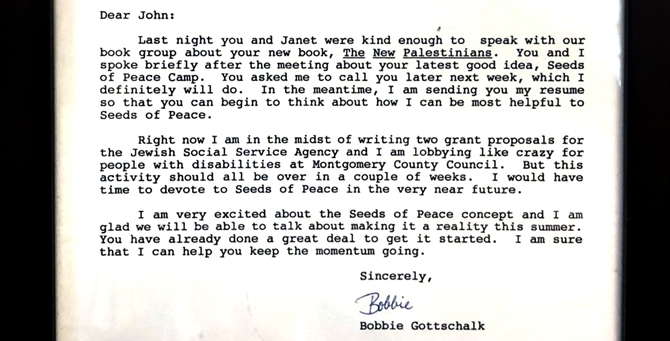

But perhaps the most important item in her makeshift museum might be a single sheet of paper hanging over the desk where she uploads photographs (sometimes an all-night process, due to a shaky wifi signal) and writes the daily Camp Reports.

Dated April 1, 1993, it’s the cover letter that she sent along with her resume to John Wallach, the founder of Seeds of Peace. He and his wife, Janet—who remains an active member of the Seeds of Peace Board of Directors today—had attended a meeting of Bobbie’s book club the previous night to discuss the book they had co-authored, “The New Palestinians.” There, he mentioned that he was also looking for an executive director for a camp he was planning to start that summer.

Whether or not you believe in fate, it was truly exceptional timing.

“I had been looking to start something from scratch for children, possibly a camp in Maine—where I had grown up going to dance camp—and he needed someone with foundational and fundraising experience,” she said. “It was a perfect match.”

Further, the idea of a Camp that allowed historic enemies to meaningfully engage with one another, to see each other as human beings, deeply resonated with Bobbie. Her grandparents had been smuggled out of the former Soviet Union in the early 1900s to escape persecution for being Jewish, and she said she grew up very focused on peace. Her mother worked for the Red Cross and eventually became a teacher, and Bobbie attended a college established by Quakers. It was there that, during the height of the Cold War, she and a few other students from her Russian literature class had the opportunity to visit Russia.

“I had been warned that my being Jewish could make me a target,” Bobbie recalled. “This stern warning, and the emotional baggage from my grandmother, put me on constant alert. Not surprisingly, I had my first asthma attack there.”

In spite of this emotional and physical tension, she dove headfirst into her program, learning, most importantly, that the Russian students weren’t so different from herself and the other American students.

“They were afraid of us, just as we were wary of them. They would take us out on rowboats and grill us about our lives in the U.S.A. They would beg us to give them a pair of our jeans,” she said. “I learned that people have a lot in common, even enemies. And none of the people we spoke with wanted to wipe us off the face of the earth, like our political leaders claimed.”

It was a formative experience for Bobbie, and was undoubtedly a key reason why John’s idea for Seeds of Peace deeply resonated with her.

Those first few years were filled with triumphs and “I can’t believe we’re pulling this off” type moments: donated air tickets and services, foreign ministries agreeing to send kids to America to meet with the “enemy,” landing a front-row seat to the signing of the Oslo Accord, and numerous features from international press, including a national broadcasting crew that followed the first five days of the very first session of Camp.

“It was terrifying!” she said of having a camera crew present. “John was determined to have the media involved from the get-go, and I never would have invited the outside world for the first five days of Camp, but the feedback was really great. I think the idea that the next generation would not have to live through what the current generation was living through really resonated with a lot of people.”

From that first session of 46 boys, the Camp and Seeds of Peace grew quickly, soon including female campers and evolving the dialogue program. In 1998, Bobbie started SeedsNet, an online list serve for Seeds that would become her first foray into serving as a digital social connector.

But even as Seeds of Peace was growing and thriving, there was no denying that things would soon be very different. John was dying, and in the summer of 2002, he finally succumbed to non-smokers lung cancer.

“When we told the Camp, I think it really scared a lot of the campers,” she recalled. “They thought, ‘Well, this is the end of Seeds of Peace.’ So we had to mourn him and deal with our own grief, but we also had to give the campers hope that this was too good to die with John.”

The next few years were extremely difficult for Bobbie and Seeds of Peace. Out of respect for John, the staff had made few preparations for a future without him as president, and it took time to find the right successor.

“It was a very hard few years, probably a textbook case of what happens when the founder, especially one who is so magnetic and the face of the organization, dies or leaves and there hasn’t been any real preparation made beforehand,” she said. “People were very reluctant to try to fill his shoes and it was very difficult.”

One of John’s successors stripped Bobbie of the majority of her duties, and many friends and family members urged her to quit.

“But I couldn’t abandon this place,” she said. “When leaders leave, it feels like the end, and I felt I would be letting the kids down.”

She did eventually step down from her staff role in 2004 and became a member of the Board of Directors. But she was still only in her early 60s and wanted to stay actively involved, so as one chapter of her life closed, she recalled advice from her mother.

“She told me that the hardest thing about getting old is losing your purpose. You have to replace it with some other purpose,” she said. “I had always wanted to have a role at Camp, and we didn’t have a photographer, so I picked up a camera.”

BEHIND THE LENS

She’s mostly self taught when it comes to taking pictures, but some of the best advice she ever received came from a sports photographer: Stand still, the action will come to you.

It usually takes about a week for the campers to stop requesting so many photos and to become accustomed to seeing Bobbie snapping photos while they canoe, climb the ropes courses, dance, or play sports.

This familiarity not only makes for better photographs, but through the camera’s lens, the former social worker is able to observe the campers’ transformations in ways she wouldn’t so easily be able to do otherwise.

“You don’t just stare at people, but with a camera, they can’t see where my eyes are. And, I feel like I am able to capture the change that comes over their faces,” she said. “They start off withdrawn, maybe hiding under a sweatshirt or physically closing themselves off, but as they began to buy into it, to see that they are safe and an enemy can become something so much more, they completely change. Sometimes I have pictures of the same person from the beginning of Camp to the end of the first week and I can’t tell that they’re the same person.”

Taking hundreds of thousands of photographs has allowed her to observe a few universal and time-tested truths when it comes to being a teenager at Camp: “Winning trumps everything,” she said with a laugh. “Many of the kids are competitive to begin with, and even if they have a fight earlier in the day, once they’re on the same team for an activity, they’re going to work together because they want to win.”

7,300 REASONS TO HOPE

Her days at Camp begin when everyone else’s does—waking up with the morning bell, lineup by the lake, breakfast, then on to activities. She rarely leaves the grounds while Camp is in session, save for Friday evenings when she makes the 80-minute drive to see her family and do laundry before returning to Camp the next morning. Since 1993 she’s only missed a handful of Camp days, and those were for family emergencies or funerals.

When she’s not at Camp, she lives with her husband, Tom, in Washington, D.C., gives lectures about Seeds of Peace at college campuses several times a year as a Woodrow Wilson Visiting Fellow, and serves on the board of several nonprofits and educational institutions.

But among her many contributions, connecting Seeds with opportunities might be among those that she most values. She’s helped countless Seeds get scholarships, apply to colleges, and launch their careers over the years, and you don’t have to look far to find stories from Seeds about how her encouragement, mentorship, and care has had an immeasurable impact on their lives.

One was Tamer, a camper from Egypt who attended the very first session of Camp.

“As a kid away from home and family for the first time, I remember finding such comfort and warmth in Bobbie as a de facto godmother,” he said. “Bobbie encouraged me to pursue my dream of studying in the United States and helped me get to college. During school holidays, Bobbie welcomed me into her home instead of letting me spend it away from family on campus. Years later, it was also Bobbie who helped me get to and through law school. It is hard to imagine what my life would have looked like without Bobbie’s constant and ongoing support, but Bobbie is also an enthusiastic advocate for each of us. Even a quick scroll through her Facebook feed would show how she beams with pride as she promotes and celebrates each Seed’s achievements.”

With 4,957 friends on Facebook—a list that she has to occasionally cull, since the site limits individual accounts to 5,000 friends—she has taken on the unofficial role of connecting and celebrating Seeds on the social media channel. Sending a birthday message (sometimes as many as 30 a day) is one of her favorite ways to stay up to date with alumni.

“I’m just so pleased with what they’re doing, I never could have predicted so many of the things,” she said. “It’s like watching a garden bloom—but imagine if you planted that garden without having a picture or knowing what the seeds were going to look like.”

Of course, the flip side of being immersed online is that she also has a front-row seat to the negative sides of social media—the ugly exchanges that can play out online, or the constant bombardment of violence and social unrest around the world.

And while there is plenty happening in the world that disappoints her, she said none of it ever discourages her. The Seeds who have come before and are working to make the world better, as well as the ones who are just beginning their journey, are reason enough to keep up hope—and for her to keep coming back.

Sitting among the pine trees beside Pleasant Lake, a soft breeze picked up when asked if, after all these years, there was anything about Camp that still took her breath away.

“I can feel all 7,000 Seeds when I’m here,” she said without hesitation. “I can see the old ones on the lake, I can hear John and Wil Smith, and I know they would still be coming here today if they could. And as long as I’m able to, so will I.”