Israel is an immigrant society. This fact is often overshadowed by the ethnic-national voices that control Israel’s political discourse.

And yet, truth remains that if an alien would have visited the country, knowing nothing about Israel and the region’s history, it would have noticed that Israel is eventually an immigrant society, that deals with much of what other immigrant societies deal with: xenophobia, racism, multilingualism, and multiculturalism.

My parents immigrated to Israel from Russia in 1990, following the fall of the Soviet Union. They immigrated along with almost a million other people from across the former states that formed the Soviet Union. Some refer to that wave of immigration as “the million who changed the Middle East,” meaning that it turned Israel politically rightward ever since. Whether true or false, it was indeed the largest wave of immigration to Israel since its establishment. It is therefore easy to understand that the effect of this wave was enormous in almost every social, cultural, and political aspect.

My parents were in their 20s when immigrating. My brother and I were born in Israel. Uncharacteristically to others from that “wave,” my parents did not insist on speaking Russian with us at home. Nor did they bring much of the Russian culture into our house. I grew up feeling Israeli, and took comfort that unlike some of my Russian-speaking peers, I didn’t pass as too Russian. To this day, my Russian is poor and full of mistakes.

During the last year, while studying in university, I founded Literatura: A Hebrew-Russian Journal. The idea first came up in my mind while participating in Connectors, a Hillel program at Tel Aviv University which supports Russian-speaking students in creating social initiatives that relate to this part of their identity.

During the last year, while studying in university, I founded Literatura: A Hebrew-Russian Journal. The idea first came up in my mind while participating in Connectors, a Hillel program at Tel Aviv University which supports Russian-speaking students in creating social initiatives that relate to this part of their identity.

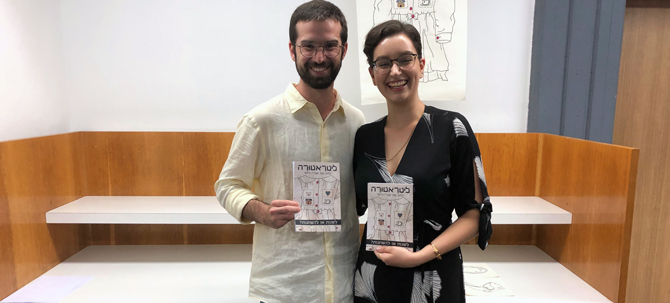

The journal aims to bring forward original Hebrew literary and artistic compositions that are created by Russian-speaking undergraduate students all over Israel. Those students are either first or second generation in the country, for whom Russian is an essential part of their everyday lives, yet their writing is done first and foremost in Hebrew and is influenced by the Hebrew literary heritage. Literatura hopes to demonstrate the contribution of this distinctive identity within the Israeli society to the Israeli literary sphere. The journal has been the best way for combining important elements of my identity: literature, creative writing, and my Jewish-Russian origin. Along with Natali, an undergrad majoring in psychology and literature, and a Seed herself, we assembled short stories, poems, plays, and translations by over 17 students to create the first issue of the journal that was published on June 5.

I believe that there is a value in putting forward writing that is produced by people in Israel that identify themselves also as Russian; for better or worse, it is still a unique voice in Israel’s cultural sphere, a voice of a generation that lives by the soundtrack of two languages: Russian and Hebrew. At this point, however, it is important to mention that the first issue’s theme did not directly focus on the immigration experience. I found it to be irrelevant when most writers were already born in Israel, and many of them do not even think of themselves in such terms. In other words, I found it to be not inclusive enough, and many, including myself, have been irritated in the first place with identifying with a sectorial journal.

Instead, I chose the following quote by the famous Russian author Leo Tolstoy to serve as the thematic base of the journal: “Everyone thinks about changing the world, but nobody thinks about changing himself.” I was introduced to this quote during my first day as a PS (second-year camper) at Seeds of Peace Camp. It stuck with me ever since. It indeed often occurred to me that sometimes it is easier to call for social change than recognizing the need for self-change. I found it therefore to be the ideal topic for a first issue of a journal that brings forward compositions that reflect the often-ambivalent desires of its writers toward assimilation.